|

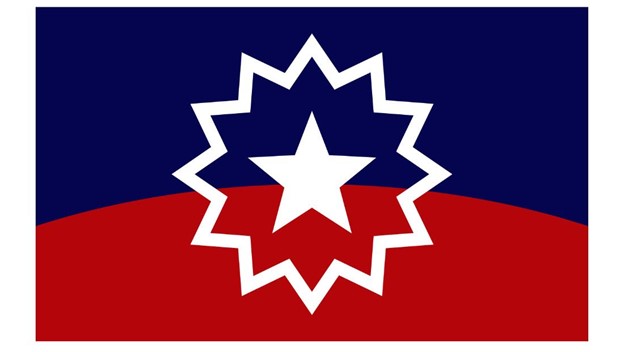

| The Juneteenth Flag |

The enslaved people of Galveston had been free for two years when they learned of the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. They were free, but still saw slaves in the mirror. The arrival of Union soldiers in 1865 allowed them to learn the truth about themselves. They were free man and women. They would never be anyone's property again. After a lifetime of sleepwalking, they were at last, "woke." They knew the truth about themselves.

I grew up in a radically segregated northern city in the 1960s. We had no Jim Crow laws, no "colored only" water fountains, but in truth, we were as sharply divided as any redneck southern town ruled by racist sheriffs and night riders.

There were no Black kids in our elementary school. No Black families at our swimming pool. No Black neighbors in our working class, immigrant rich suburb of Pittsburgh. As far as I know, Dad had one Black union brother at the newspaper where he was a printer for 40 years. Our church never acknowledged their existence.

The only dark faces I ever saw on my street belonged to the garbage men who rode the back of the big trucks and slung the neighborhood's trash cans high on their shoulders to carry them to the street. They were strange, silent giants who worked, but never spoke. They "knew their place."

"Knowing their place" was the official expectation of "the coloreds" from the good Christian men and women in our community. The kindest among white folk would say, "I have no problem with them, as long as they know their place." Some others would have happily seen them all sent "back to Africa."

When my family would gather for holidays, words like nigger and coon were used candidly and casually. My uncles would share their opinions on the lazy athletes, immoral criminals, and trouble making "jigaboos" who lived in the projects and the ghetto on "The Hill":the historically Black neighborhood in our city. My grandma used to share the story of a childhood trauma she experienced when as a toddler, she pointed to a stranger and said, "Look, Mamma, Niggy-man! Niggy-man!" and the man brandished a knife with which he would have killed them if there weren't so many white people around. She used this story to justify a lifetime of what we used to call "prejudice" against anyone whose ancestors may have been African.

My dad, who was far from liberal, and in spite of all the influences around him, raised his children to swim against the racist tide in which we lived. "You don't judge people because of color or religion. You judge them one at a time." It wasn't a fancy philosophy, but it was the first time I ever heard an adult suggest that there was another way to look at strangers than to sort them into groups by color, nationality or church. The lesson stuck.

I was a clumsy young liberal. I remember being curious and fascinated when I learned, at my first experience in an integrated swimming pool at Boy Scout camp, that the colored kids were pink on the palms of their hands and the souls of their feet. I tried to make friends with one of the four Black kids in my high school of 3000, but he always seemed a little wary and cautious as if he didn't understand that I wasn't like the other white kids who mocked his music, his hair, and his broad lips. My small Presbyterian college wasn't much better. The black kids were mostly athletes. They were clannish and sat together in the dining hall. I couldn't understand. They seemed to segregate themselves without even being asked to.

There were a few exceptions: Actors, mostly, since theatre was the world where I spent most of my time. I viewed them as beautiful and exotic. I loved the rhythm and cadence of their voices and the way their muscular arms and round hips moved on the stage. We made friends. Worked together. Partied together. Hung out. But I always felt like an outsider. Somehow I knew that when my black friends were alone, with no white people around, there was something they shared that I knew nothing about.

Fenton was a stage manager on my first national tour. He was a big, funny man with coffee colored skin and a taste for pretty women, good weed, and a rolling poker game that kept us sane at the back of the bus as we traveled between cities. He had been drafted and sent to Viet Nam, and one night, over the remains of a bottle of Cuervo we finished together, he told me this story. He was on guard duty, staring into the jungle, looking for trouble. He needed to take a piss, and put down his weapon while he relieved himself. In the leaves, he heard a cartridge drop into its chamber. He looked up to see a shadow with a weapon aimed at his heart. Fenton froze, knowing he was about to die in those woods with a bullet in his chest and his dick in his hand. Instead of a flash, a whisper of broken English seemed to come from the muzzle of the rifle.

"Not your war, Brother. Not your war."

The shadow disappeared into the vegetation as suddenly as he had materialized, but his terrifying message had been delivered. Fenton understood. The Viet Kong new that Black Americans were fighting the white man's war. It was something he carried with him long after returning home to Harlem. I realize now that this was probably a psychological tactic used on a lot of Black soldiers in that rainforest. But I also realize what an honor it was for Fenton to trust me enough to share that story with me. It was an intimacy I've never forgotten and I still love him for it.

I guess the moment really saw my own heart for the first time was during a break between shows at an outdoor music festival in New York. I was walking to a coffee shop with one of the musicians when I mentioned that I grew up in Pittsburgh. He knew the city and its jazz music scene well, and I shared a story of an evening I spent with some high-school friends at a bar, listening to music we had never heard before, and loving it. Laughing, I described the club as a place where a group of white boys ought not to be in the middle of the night. My companion did not laugh at my attempt at self-deprecation.

"Why? Where were you?"

"I'm not sure. Up on The Hill, someplace."

"Man. That's just the neighborhood. Nothing was going to happened to you." And then he cut me open and showed me something I didn't want to see.

"See, that's how racism works. It's insidious. It gets up underneath your thoughts and your intentions. It's in there, even when you don't want it to be. We tell ourselves to be afraid, and so we are. Man. You were just in the neighborhood."

And that's when I woke up to my own bigotry. I hadn't really risen above the prejudice of my family and community. I wasn't superior. I'd just covered it over. Racism was still there, waiting to pop us like a blister when I least expected it. I wasn't color-blind. I was blind to myself. I don't remember that man's name. But I think about him. A lot.

In a way, he set me free.

The great German novelist, Goethe said in Maxims and Reflections, "No one is more of a slave than he who thinks himself free without being so." So maybe, the best racist is the one who thinks himself woke. By showing me my own racism, that musician showed me how to be better than myself. He showed me how to recognize it and not let it distort my vision of the world or of myself.

My character was formed in the industrial North in the 1960s. I heard a lot of things about people I did not know. Those early lessons are still with me. They tug and tempt me when I encounter things and people I do not understand. Sometimes, the prejudices of my youth prevail, sometimes not. I still have a lot of waking up to do.

In a very real sense, Juneteenth does not belong to white folk. It belongs to the people who waited years to hear the news of emancipation, and then waited more than a century for their country to recognize the significance of that day... the day people who thought they were slaves learned to be free.

Still, we can all learn from the lessons of Juneteenth. We can recognize our own bondage to prejudice. We can acknowledge the heritage of bigotry that distorts our own vision and behavior. We can awaken to the truth inside, and learn how to live with it without letting it shape our relationships. Finally, we can forgive ourselves and each other for our ignorance, and walk with just enough grace to keep trying to do better.

We can wake up.

We can be free.

We can hope.

Yes, we can.